I was there 70-71. That was the year we lost a generator at top

camp, water and the sewage system froze up. Poop in a can what

was done. My job as driver was to get the mail, diesel fuel ,

and people to top camp. One time I ran into a white out at 6 mile

couldn't go anywhere for 4 hours before it broke. The dozer had

to get me and my truck full of people out. Some of my stories

could go on forever. Sure was glad to see Wieny bird bring in

the mail, and the chopper that came when it was my turn to leave.

figmo.

|

|

|

|

The old adage that "misery comes in threes" gained

some credence recently at Indian Mountain Air Force Station when

the forces of nature began a chain reaction which beset station

personnel with a triplet of major problems.

Indian Mountain, one of Alaskan Air Command's remote radar stations,

is located in the desolate Alaskan interior about 165 miles northwest

of Fairbanks. It is home for the 708th Aircraft Control and Warning

Squadron, part of the North American Air Defense Command's web

of early warning stations.

The station is divided into two areas: "top camp," atop

the 4,200 foot peak consists of three radar towers, troop housing,

an operations building and a standby power plant. "Bottom

camp," about 12 miles away, provides electricity and supplies.

The station's gravel air strip is also there.

Between the two camps, about a quarter-mile down the mountain,

stands top camp's only water supply - a 1.2 million gallon tank

and pump house. This is where their problems began.

Top camp became isolated because of extremely high winds and blowing

snow. While the men were "imprisoned" by the weather,

high winds blew open a door to the pump house.

With a wind-chill factor approaching 100 degrees below zero, the

pump house's heat was quickly lost. Everything inside was soon

frozen, and top camp's water supply was completely shut off.

The second major problem began a few hours later. Station engineers

detected trouble somewhere along the power line running up from

bottom camp. Unable to withstand outside weather to investigate

the source of either problem, the station was forced to switch

to emergency power.

The following day, with no water, top camp's two boilers atomatically

shut down. Again emergency procedures were begun to overcome the

problem.

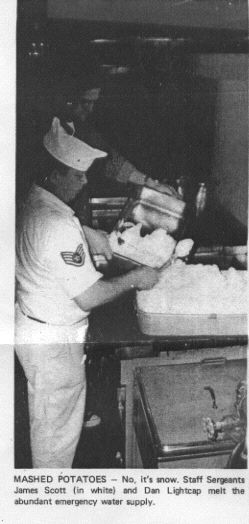

Snow became the only water source. Using what water could be obtained

from melted snow, the boilers were manually pumped. This didn't

solve the heating problem. The men at top camp were soon wearing

their special Arctic weather gear inside.

After nearly a week, the weather cleared enough to allow investigation

of the water supply problem. The next day a portable heater was

installed in the pumphouse, and the frozen pipes and valves were

thawed by evening.

But another problem had arisen. One of four 7-ton diesel generators

providing emergency power broke down, threatening top camp with

a complete power loss. Top camp's manning was reduced to a skeleton

force. Power consumption was cut to a bare minimum.

Severe weather again returned and brought still more problems.

The portable heater in the pump house failed. All the plumbing

fixtures were frozen again.

Informed of the rapidly deteriorating situation at Indian Mountain,

Col. Albert M. Doherty, commander of the 21st Civil Engineering

Squadron at Elmendorf AFB, alerted technicians from one of his

mobile engineering teams.

Several attemps to aid the men were unsuccessful. Engineers aboard

a C-124 Globemaster were unable to land on the gravel strip.

Several days later three plumbing specialists, a lineman and their

hand tools were flown into the station aboard an H-3 from the

5040th Helicopter Squadron. The weather cleared enough to allow

inspection of the power lines and repairs were made on two loose

connections. Power returned to normal at the summit.

Investigation of the pump house revealed another problem to overcome.

Although every fitting inside the shelter had frozen, the waterline

leading from the tank was still open. An attempt to replace the

frozen and cracked shut-off valve inside the pump house would

leave the tank free to dump top camp's only water supply.

The plumbers agreed the solution would be to turn off electicity

to the outside pipe heater and let part of the lead-on pipe to

freeze to form an ice block. Nature again interfered. Before the

water was able to freeze again, the temperature rose. The water

wouldn't freeze.

This development left only one solution - plug the pipe from inside

the tank. And so a unique event took place at the isolated station.

A professional scubadiver was helicoptered in from Anchorage.

Suited up in his gear, he dived into the tank and plugged the

pipe.

The water is continually circulated and slightly heated so it

won't freeze.

With the tank plugged, the plumbers repaired and replaced the

essential pumps, pipes and valves. The divers jumped back into

the tank and removed the plug; but when the water was turned on,

it was discovered several fittings at top camp had also frozen

and cracked. Once again the diver cut off the water supply while

repairs were made.

After two weeks without adequate water, proper sewage facilities

or sufficient heat, repairs finally were complete and top camp

was back to normal.

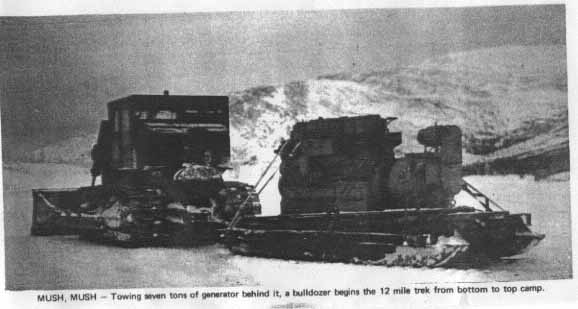

In the meantime, a replacement generator, which was too heavy

to be hauled by helicopter, and three diesel engine specialists

were trying to reach the station. After many attempts by a C-124

to land at Indian Mountain, the men and most of their equipment

were landed at Galena AFS. Finally they were shuttled to the mountain

in three chopper trips while the lightened Globemaster finally

landed at bottom camp and unloaded the generator.

The problem of getting the generator to top camp still remained.

The only means available was a tractor-towed sled. Severe weather

struck the next day postponing the trip up the mountainside. After

two days of blizzard, the weather broke and the generator was

hauled up the mountain in a three-hour trip. The machine was quickly

installed, and Indian Mountain was again completely prepared for

its radar mission.

Reflecting on the trying experience, Maj. Paul J. Desroches, the

station's commander, held nothing but praise for his men. "I'm

extremely proud of all of them," he said. "They displayed

a fine spirit and high degree of professionalism throughout the

difficulties. The fact that the station passed a no-notice operational

readiness inspection with flying colors during this period is

proof of the outstanding caliber of their work," he emphasized.

The saga at Indian Mountain is over now. Their mission goes on.

Although faced with hardships and severe Arctic weather, the mountaineers

continue to provide "top cover for America."