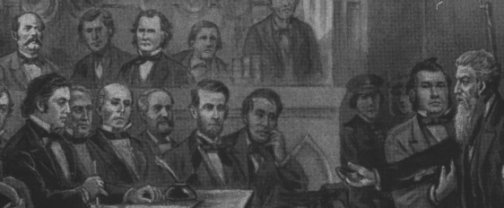

Lewis Washington (upper left) was the main

witness against

John Brown(right).

The statement of Colonel Lewis W. Washington

at the trial of John BrownBetween one and two o'clock on Sunday night, I was in my bed at my house, five or six miles from Harper's Ferry ; I was awakened by hearing my name called in the hall ; I supposed it was some friends arrived, who, being acquainted with the house, had come in through the kitchen without making any noise ; I got up and opened the door into the hall, and before me stood four men, three armed with Sharpe's rifles, leveled and cocked, and the fourth-this man Stephens-with a revolver in his right hand, and in his left a lighted flambeau, made of pine whittlings.

As I opened the door, one of the men said: "Is your name Washington?" Said I, "That is my name." Perhaps also Cook, who was of the crowd, also identified me, as he told me afterward he was taken there for that purpose. I was then told that I was a prisoner, and one of them said, "Don't be frightened," I replied, "Do you see anything that looks like fright about me ?" "No," he said, "I only want to say, that if you surrender and come with us freely, you are safe."

I told them I understood that sufficiently and there was no necessity for further explanation; but I was struck with the number of men sent against me, and asked what need there was of so many, as there was no danger of an unarmed man in his night-shirt resisting an armed foes. I was told to put on my clothes, and of course complied. "Perhaps," said I, "While I am dressing, you well be so good as to tell me what all this means?" I inquired what the weather was outside, and one of them advised me to put on an overcoat, as it was rather chilly. Another said they wanted my arms, and I opened the gun-closet for them to help themselves.

They then explained their mission, which they represented to be purely philanthropic, to wit, the emancipation of all the slaves in the country. After I was dressed, Stephens said to me, "Have you got any money?" I replied, "I wish I had a great deal." "Be careful, sir," said he. I told him if I had money I knew how to take care of it, and he could not get it. Said he, "Have you a watch?" My reply was, "I have, but you cannot have it. You have set yourselves up as great moralists and liberators of slaves; now it appears that you are robbers as well." "Be careful, sir," said he again.

I told them I was dressed and ready to go. They bade me to wait a short time and my carriage would be at the door. They had ordered my carriage for me and pried open the stable-door to get it out. They had harnessed the horses on the wrong side of each other, and I tried to induce them to correct the mistake, which they did after driving a short distance, but still, being harnessed wrong, and rather spirited animals, they would not work well. My servant, whom they had forced along, was driving.

I suspected they were only robbers, and was expecting all along that they would turn off at some point, but they drove directly to the armory. Brown came out and invited me in, saying there was a comfortable fire, and I shortly afterward met with Mr. Allstadt, whom they had arrested on the way and brought along in my buggy wagon. While coming along, the horses being restive, I got out and walked up a hill with one of the men, who took occasion to ask my views on the subject of Slavery in the abstract. I declined an argument on the subject, but he still pressed it upon me, and I was obliged to refuse the second time. Brown told us to make ourselves comfortable, and added, "By and by I shall require each of you, gentlemen, to write to some of your friends to send a stout Negro man in your place." This was by way of ransom. He told us he must see the letter before it was sent, and he thought after this was effected they could make an arrangement by which we could return home. I determined in my own mind not to make the requisition but he never made application for it, having other matters, before the day expired, attracting his attention.

My sword, which had been presented by Frederick the Great to General Washington, was taken from my house, with other arms. This man Cook had been at my house some time before and seen the arms, and at that time I beat him at shooting, and he told me I was the best shot he had ever met. On the way to Harper's Ferry he asked me if I had shot any since, and made an apology for being with this party after being so well treated by me. I told him it 'was of no consequence about the apology, but I would ask one favor of him, which was to use his influence to have returned to me the old sword and an old pistol, which, in the present improved state of arms, were only valuable in consideration of their history. He promised to attend to it, and shortly after reaching the armory I found the sword in Old Brown's hands. Said Brown, "I will take especial care of it, and I shall endeavor to return it to you after you are released." He carried the sword in his hands all day on Monday, until after the arrival of the military.

Upon the first announcement of the arrival of the militia, Brown came into the room and picked out ten of us, whom he supposed to be the most prominent men. He told us we might be assured of good treatment, because, in case he got the worst of it in the fight, the possession of us would be of service in procuring good terms; we could exercise great influence with our fellow-citizens; and as for me, he knew if I was out I should do my duty, and, in my position as aid to the Governor I should be a most dangerous foe. Then we were taken into the engine-house and closely confined. Two of our number went backward and forward repeatedly to confer with citizens during the negotiations, and finally remained out altogether, leaving the eight who were inside when the building was assaulted and captured by the marines. During Monday various terms of capitulation were proposed and refused, and at night we requested our friends to cease firing during the night, as, if the place should be stormed in the dark, friends and foes would have to fare alike. In the morning Capt. Simms, of Frederick, announced the arrival of the United States Marines. During the night he had brought in Dr. Taylor*, of Frederick, to look at the wounds of old Brown's son. The surgeon looked at the man, and promised to attend him again in the morning if practicable, but about the time he was expected hostilities had commenced.

Colonel Lee, who commanded the United States forces, sent up Lieutenant Stuart to announce to Brown that the only terms he would offer for surrender were, that he and his men should be taken to a place of safety and kept unmolested until the will of the President could be ascertained. Brown's reply was to the effect that he could expect no leniency, and he would sell his life as dearly as possible. A few minutes later the place was assaulted and taken. In justice to Brown, I will say that he advised the prisoners to keep well under shelter during the firing, and at no time did he threaten to massacre us or place us in front in case of assault. It was evident he did not expect the attack so soon. There was no cry of "surrender" by his party except from one young man, and then Brown said, "Only one surrenders." This fellow, after he saw the marines, said he would prefer to take his chance of a trial at Washington. He had taken his position, and fired one or two shots, when he cried "surrender." There were four of Brown's party able to fight when the marines attacked, besides a Negro, making five in all. This Negro was very bold at first, but when the assault was made, he took off his accoutrements, and tried to mingle with the prisoners, and pass himself off as one of them. I handed him over to the marines at once, saying he was a prisoner at all events.* He is refering to Dr. William Tyler Jr. a Frederick Surgeon.