On October 16, 1859, John Brown and 18 men entered Harper's Ferry and captured the federal armory. After having secured a large cache of weapons, Brown ordered his men to obtain local hostages and bring them back to the armory. Their first stop was Beallair, the home of Lewis Washington, son of George Washington's grandnephew.

Lewis Washington was an honorary colonel because

of his service to the

Commonwealth of Virginia.

Because of extensive reconnaissance,

the raiders were able to enter Beallair

and capture Lewis Washington.

escaped capture. His account

is the only one published by

a member of Brown's party.

According to Anderson: "During this time, Washington was walking the floor, apparently much excited. When the Captain came in, he went to the sideboard, took out his whiskey, and offered us something to drink, but he was refused. His fire-arms were next demanded, when he brought forth one double-barreled gun, one small rifle, two horse-pistols and a sword. Nothing else was asked of him. The Colonel cried heartily when he found he must submit, and appeared taken aback when, on delivering up the famous sword formerly presented by Fredrick to his illustrious kinsman, George Washington, Capt. Stevens told me to step forward and take it. Washington was secured and placed in his wagon, the women of the family making great outcries, when the party drove forward to Mr. John Allstadt's. After making known our business to him, he went into as great a fever of excitement as Washington had done. We could have his slaves, also, if we would only leave him. This, of course, was contrary to our plans and instructions. He hesitated, puttered around, fumbled and meditated for a long time. At last, seeing no alternative, he got ready, when the slaves were gathered up from about the quarters by their own consent, and all placed in Washington's big wagon and returned to the Ferry.

Washington testified that On the way back to Harpers Ferry, the raiders took more hostages. "At the house of Mrs. Henderson, widow of Richard Henderson, they stopped the carriage just in front of the house; there were four or five daughters in the house who had recently lost their father, and I remarked to the party in front of me, there is no one here but ladies, and it would be an infamous shame to wake them up at this hour of the night." The raiders proceeded to the next house, letting Mrs. Henderson and her daughters enjoy a good nights sleep.

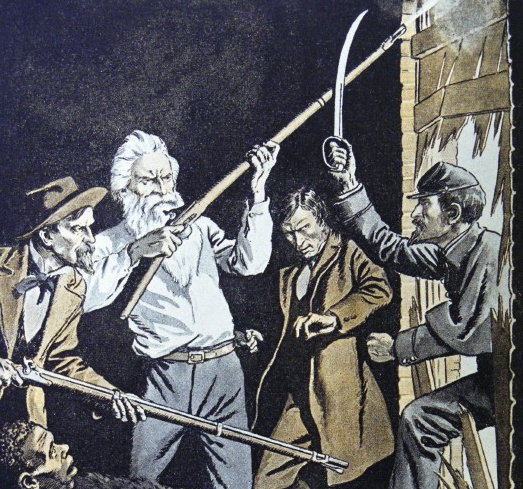

of John Brown by Lieutenant Green.

In December 1885, The New American Review published an eyewhitness account by Lietenant Israel Green. He descripes the aftermath of the fighting."I saw very little of the situation within until the fight was over. Then I observed that the engine-house was thick with smoke, and it was with difficulty that a person could be seen across the room. In the rear, behind the left-hand engine, were huddled the prisoners whom Brown had captured and held as hostages for the safety of himself and his men. Colonel Washington was one of these. All during the fight, as I understood afterward, he kept to the front of the engine-house. When I met him he was as cool as he would have been on his own veranda entertaining guests. He was naturally a very brave man. I remember that he would not come out of the engine-house, begrimed and soiled as he was from his long imprisonment, until he had put a pair of kid gloves upon his hands. The other prisoners were the sorriest lot of people I ever saw. They had been without food for over sixty hours, in constant dread of being shot, and were huddled up in the corner where lay the body of Brown's son and one or two others of the insurgents who had been killed."

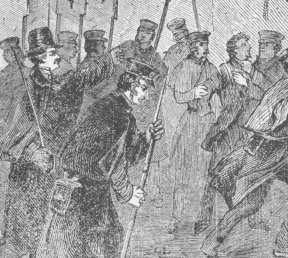

Lewis Washington assists

the marines

by identifying the raiders.

This is a detail from a 1859

newspaper drawing.

In July 1883, Century magazine published an eyewitness account of the raid by Alexander Boteler, who was a good friend of Lewis Washington.

"There was a shot, some inarticulate exclamations, and a short struggle inside the engine-house, and then, as our rescued friends emerged from the smoke that filled it, followed by marines bringing out the prisoners, the pent-up feelings of the spectators found appropriate expression in a general shout

As Colonel Lewis Washington came out I hastened to him with my congratulations, and to my inquiry:

'Lewis, old fellow, how do you feel?'

He replied, with characteristic emphasis:

'Feel! Why, I feel as hungry as a hound and as dry as a powder-horn; for, only think of it, I've not had anything to eat for forty odd hours, and nothing better to drink than water out of a horse-bucket!/

He told me that when Lieutenant Green leaped into the engine-house, he greeted him with the exclamation: 'God bless you, Green! There's Brown!' at the same time pointing out to him the brave but unscrupulous old fanatic, who, having discharged his rifle, had seized a spear, and was yet in the half-kneeling position he had assumed when he fired his last shot. He said, also, that the cut which Green made at Brown would undoubtedly have cleft his skull, if the point of his sword had not caught on a rope, which of course weakened the force of the blow; but it was sufficient to cause him to fall to the floor and relax his hold upon the spear, which, by the way, I took possession of as a relic of the raid."

Alexander Boteler was

the congressman from Jefferson County at

the time of the raid.